“Has the evolution of the female image come to a halt?” — Two eras of thought revealed through this sense of unease

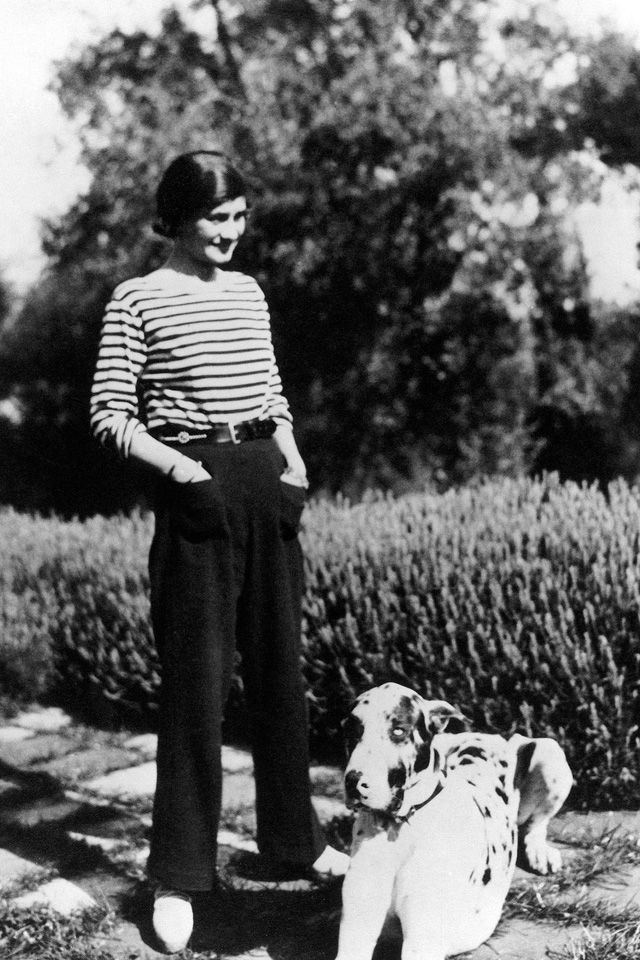

The other day, I watched the documentary Coco Chanel: The Woman Who Fought Against Her Time on U-NEXT.

It depicted how Chanel broke through the male-dominated society of her era and introduced concepts of freedom and independence for women — a testament to the very foundation of the CHANEL brand.

Watching it reminded me once again that CHANEL has been a brand that continuously offers freedom and new ways of living to women throughout the 20th century.

Naturally, that experience led me to want to write an article tracing the evolution of the female image as portrayed in CHANEL’s runway shows.

As the documentary suggested, CHANEL has always stood by women—sometimes following their path, and at other times, boldly leading the way. But when I began to explore this theme more deeply, I encountered an unexpected sense of unease.

Up until Coco Chanel’s era, the female image was clearly evolving. Society was changing, and fashion moved in tandem.

But during Karl Lagerfeld’s time, I found myself wondering: Was this truly an evolution?

That question made me consider a different perspective—perhaps it is precisely the appearance of a halted evolution that holds deeper meaning.

That is, an entirely new approach: one in which “transformation” itself becomes the material to be restructured and reinterpreted.

In this article, I aim to explore the profound philosophy woven into the CHANEL maison by contrasting two visions of womanhood—Coco’s ever-changing woman and Karl’s seemingly immutable one.

1. CHANEL Transformed the Image of Women — The Revolution of Coco Chanel

What Coco Chanel brought into the world of fashion was not merely a new style.

Her clothing is often seen as a symbol of freedom for women’s bodies, and a statement of liberation from the roles society had long imposed on them.

- Rejection of the corset: liberation from physical constraint

- Introduction of jersey fabric: ease of movement = a body with agency

- The little black dress: transforming the color black from mourning to modern elegance

- Sailor pants and pantaloons: masculine elements reframed as symbols of female freedom

The little black dress, for example, redefined “black” — once reserved for mourning — into a modern, refined garment for everyday life.

Source:https://www.vogue.co.jp/fashion/trends/2018-10-31/black-dress/cnihub

In the 1930s, Chanel reimagined pieces like sailor pants for resort wear, and adapted naval uniforms into fashion through her creation of the marinière (a sailor-striped jersey shirt). These garments became new icons for “women in motion.”

Source:https://www.chanel.com/jp/about-chanel/gabrielle-chanel/

Behind these designs lay the backdrop of women’s increasing social participation after World War I, and the rise of a new value system centered on independence. Through her designs, Coco Chanel embodied this emerging image of the modern woman — one who lived freely, intellectually, and beautifully — and redefined how women would carry themselves in a changing world.

2. “Did Change Come to a Halt?” — A Subtle Discomfort with Karl Lagerfeld

In 1983, Karl Lagerfeld was appointed artistic director of CHANEL.

The first challenge he faced was how to revive a brand that had already become a legend of the past.

Rather than pursuing innovation, Lagerfeld chose a different path: one of quotation and reconstruction.

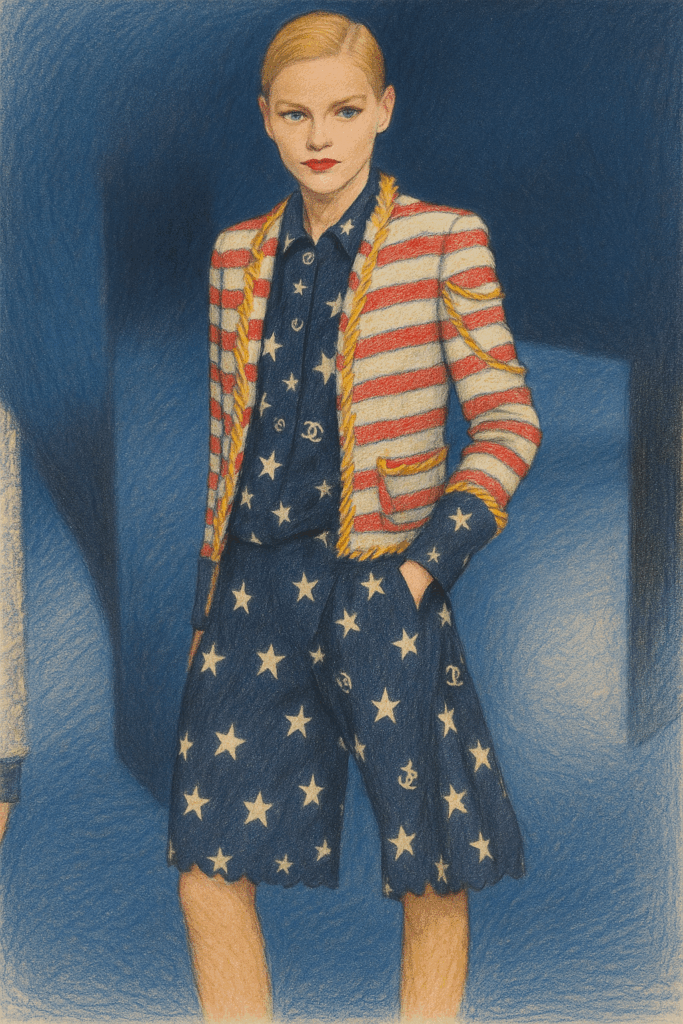

- Tweed mini dresses and shorts: boldly rejuvenating Coco’s signature material

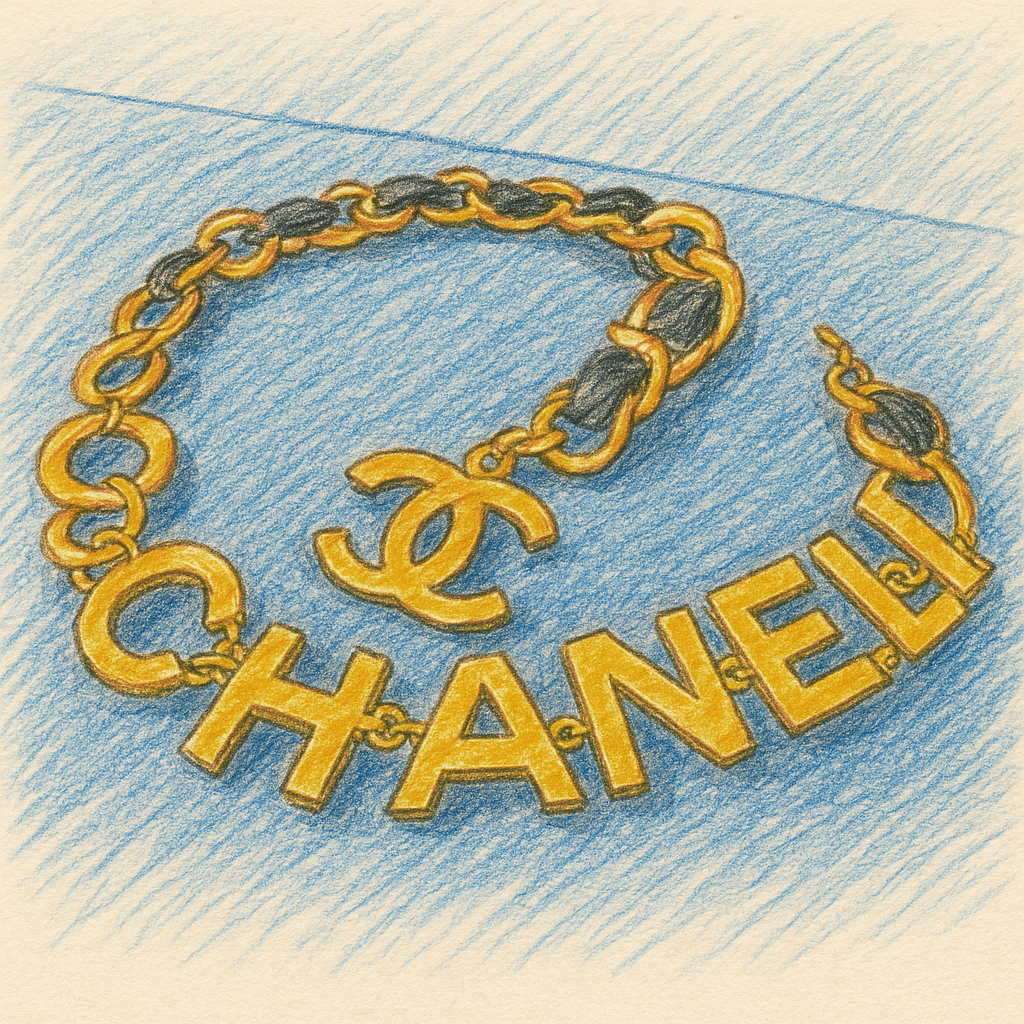

- Logo-emphasized belts and accessories: turning brand symbolism into playful motifs

- Runway stage productions: rocket ships, supermarkets, launch pads, and more

These were not representations of a linear evolution of womanhood, but rather a curated diversity—and what could be described as the playful recontextualization of icons.

Lagerfeld took CHANEL’s classic tweed and transformed it into mini-length silhouettes and shorts. By dressing young models in these looks with a streetwear sensibility, he presented a modern female image unbound by age or class.

Representative collections: Spring/Summer 2008 and 2010 Ready-to-Wear.

Just as he reshaped the overall impression of the CHANEL brand, Lagerfeld infused his logo designs with a spirit of playful reinvention. Oversized “CHANEL” and interlocking “CC” logos adorned belts and necklaces, presented with deliberate visibility.

This postmodern approach—where brand identity became self-aware, even ironic—turned CHANEL into a fashion house that was unafraid to parody its own prestige.

Representative collections: Spring/Summer 1993 Ready-to-Wear and various accessory lines in the 2000s.

CHANEL’s shows became more than fashion presentations; they were immersive experiences, articulating the worldview the brand sought to convey to women.

Supermarkets, rocket launches—these grand stage sets served as metaphors for consumerism, environmental themes, and futurism, positioning CHANEL as a space to question the spirit of the times that shaped female identity.

Representative stage designs:

Supermarket: Fall/Winter 2014 Ready-to-Wear (transformed venue into a CHANEL grocery store)

Rocket launch: Fall/Winter 2017–18 Ready-to-Wear (Grand Palais)

Tweed, logos, the little black dress—Lagerfeld refused to treat CHANEL’s sacred icons with untouchable reverence. Instead, he recontextualized them with humor, critique, and a sense of the everyday. This mode of play, of thoughtful détournement, was quintessentially Lagerfeld.

Women, in his world, were not just changing—they were celebrated for their capacity to change.

That phrase—“a being celebrated for change”—captures the essence of how Lagerfeld viewed the modern woman.

Not as a fixed ideal, but as someone whose shifting identities and expressions are not only accepted, but affirmed.

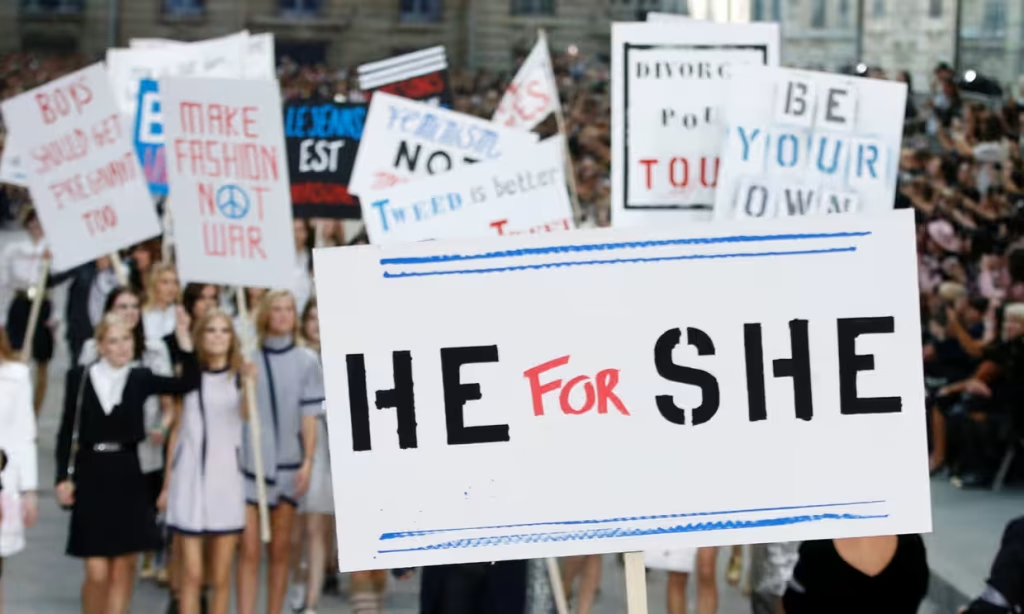

For instance, in the Spring/Summer 2015 Ready-to-Wear collection, CHANEL staged a dramatic “women’s rights protest” on the runway, where models marched with placards in hand.

Dressed in three-piece suits and long, masculine coats, they embodied women as empowered individuals who speak out with confidence and autonomy.

Source:https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2014/sep/30/karl-lagerfeld-chanel-show-paris-fashion-week

In the previously mentioned Fall/Winter 2017–18 Ready-to-Wear collection, a giant rocket was installed inside the Grand Palais.

Futuristic sequin dresses were paired with traditional tweed, symbolically affirming both CHANEL’s classic vision of femininity and a forward-looking image of the woman who charts her own path.

In the Fall/Winter 2004 Ready-to-Wear collection, masculine tailoring, hats, and tie-inspired accessories were introduced.

With a theme centered on the fusion of masculine and feminine elements, the collection presented a vision of womanhood that transcended traditional gender boundaries.

Source https://www.vogue.com/fashion-shows/fall-2004-ready-to-wear/chanel

Each of these collections did not so much aim to redefine the image of women, but rather to beautifully stage and celebrate the very act of transformation itself.

They can be seen as embodying the concept of “a being celebrated for her capacity to change.”

3. When the Evolution of the Female Image Becomes a Philosophical Question

As discussed in the previous section, Karl Lagerfeld did not merely inherit CHANEL’s iconic elements—he quoted, reinterpreted, and at times exaggerated them, restructuring their meaning within a contemporary context.

This process of reconstruction suggests that fashion, far from being just a series of trends, serves as a response to deeper questions:

What is a woman? How is femininity constructed and expressed?

For example:

- The mix of masculine and feminine codes in the Fall/Winter 2004 collection blurred the boundaries of gender roles.

- The pairing of sneakers with tweed in Spring/Summer 2014 hinted at the dismantling of class consciousness.

- The excessive use of logos from the 1980s onward suggested a satirical critique of consumer culture.

These were not just garments—they were signs, and what we might call the movement of signs.

In other words, the same motifs appeared repeatedly, each time layered with new meanings and perspectives, reframed through shifting cultural contexts.

Evolution, in this case, was no longer a linear flow, but a question of how things are signified.

In the Spring/Summer 2014 Haute Couture show, all 65 models walked the runway in sneakers.

By combining sneakers with CHANEL’s formal tweed, Lagerfeld disrupted the traditional codes of elegance.

This bold styling choice captured the spirit of a younger generation—one that desired greater freedom and casual sophistication—and simultaneously challenged old hierarchies and conventions around class and formality.

Source:https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2014/jan/21/chanel-couture-trainers-cara-delevingne-karl-lagerfeld

4. The Changing Woman, the Timeless Icon — Two Philosophies at the Heart of CHANEL

Coco Chanel and Karl Lagerfeld.

They each portrayed the CHANEL woman in entirely different eras, through entirely different methods.

Coco depicted a woman who changed the times.

Karl presented a symbol that questioned the times.

Both approaches were not merely about clothing—they were philosophical practices. In their hands, CHANEL became a language for expressing thought itself.

In Closing

As I set out to trace the evolution of the female image, I encountered an unexpected beauty: the aesthetic of reconstruction that dwells within constancy.

Coco gained freedom through continuous transformation.

Karl played with the power of a symbol that remains unchanged.

In their contrasting visions lies the true essence of CHANEL: a brand that never stops asking what it means to be a woman.

At PhiloMode, I hope to continue exploring these questions—unfolding the design of thought itself.